Saleswhale Blog | 33 Min Read

Are you tired of spending money on marketing experiments that don't work?

Jason Widup, VP of Marketing at Metadata, is a marketing leader that I look up to, and have been following for some time.

He ran a pretty crazy marketing experiment recently which turned $266,000 of marketing spend into $5.3M in sales pipeline and $1.3M closed-won revenue (and climbing).

You can read more about it here.

This got me thinking.

What if, instead of talking about what he did (tactics, metrics, campaign execution).. which is likely to be irrelevant and copied relentlessly by the time you see this -

Wouldn't it be way more interesting to interview Jason about his process?

If you are interested to get your hands on the marketing experiments template that Jason uses (with some minor tweaks), you can download it here. You will get -

One of the big benefits that I have is that our CEO is a big believer in experimentation. He probably pushes me to do more experimentation that I would be comfortable with!

He probably only said "no" to a grand total of one idea I've ever proposed. But in hindsight, that was a pretty edgy idea.

When it comes to experimentation, it's a cultural shift first. You can't be a marketer who is all about experimentation, and join a company where it's not OK to fail.

Experimentation means failure. Well, I mean that's not exactly the definition if you look it up. But you get the point.

If you are a marketer who runs quite a bit of experiments, it means that you probably fail a lot. You have to iterate, and figure out what works.

I've been a part of organizations in the past where stakeholders get anxious and nervous when experiments fail. Marketing then reverts back to the comfort of what they have been doing all along, and regress to activity-based goals instead of performance-based goals.

I built an open-source demand model to help estimate how much budget I would need to hit my goals, and I try to have some discretionary amount set aside every quarter for experimentation.

But back to your question, I would argue that it's even more important to experiment if you realize you are going to fall behind.

It's counter-intuitive, and requires a little faith.

But imagine you know that you are not going to hit your goals no matter what based on the tried-and-true stuff, based on your historical demand model. Then, I would argue that putting your best foot forward on a solid experiment with 20% or more of your remaining budget could be a good move.

This also helps you in future quarters, because you can then take the learnings to determine if these experiments are viable candidates to double down on.

Guillaume Cabane is a dear friend and mentor of mine. Through my mentorship with him, he showed me an experiments framework he was using on Airtable. It was amazing.

The framework is fairly formalized. And I realized that as we scaled the team and number of experiments we were doing, it became a necessity. Managing it ad-hoc and with data strewn in multiple places just wasn't working anymore.

This framework gives you a way to collect all the ideas internally, and throughout the organization, using a form you provide to them (this helps with CEOs who like to throw ideas over the transom).

It forces you to think about your impact & success metrics, and which parts of the funnel you are trying to impact. You add a bunch of data points to these experiment ideas, and it automatically helps you stack-rank the ideas.

You keep track of the statuses of various experiments that are running. You then make a decision if you want to promote the completed experiment to an evergreen marketing initiative, or to send it to the graveyard.

Gabriel:

Great to have you here Jason in our Masterclass finally.

Jason:

I was just so pleased and tickled to be invited. So yeah, I am looking forward to just talking and maybe helping some folks out with how to think about experimenting.

Gabriel:

Yeah. So let's dive right into it. So, you know, in the teaser post on LinkedIn, we have over 300 comments and reactions. People want to find out about this crazy experiment that you ran. With $200+ budget. And you have $5.3M in pipeline, and $1.2M in closed-won revenue..tell us all about it. How did that come about?

Jason:

Yeah. So I'll talk about the situation that drove it first and then we can talk a little bit about what the campaign actually was.

So it was last year, it was April. I think we all kind of know what was happening in April last year. Things were crazy. We had a virus. For me, I had actually just started full-time at Metadata I think on April 1st. But I had been consulting and advising Metadata for six months prior to that. And so I understood what we were able to do over that six months and, you know, the number of demos and the demand and what that looked like. Now I was just scraping the surface back then because I was only part time and I was the only marketer really, maybe a third time marketer.

So I came into the role and I had negotiated things like, well, how much budget are we going to have to spend in marketing? You know, all those things. And I land and it's like Oh no, everything's closing down. Everybody's not sure what to do with their budgets. And so I actually had my budget cut that we had originally agreed to before I came on full time. I had to cut by I think it was like 60 percent.

Gabriel:

Oh Boy!

Jason:

But the goals didn’t change. “Well, our goals are the same but let's try and meet those goals with a lot less spend.” And so I was nervous but excited. And so that's kind of one of the first things I'd like to talk about - how constraints can actually be a drive to innovation, kind of have a lead into innovation.

But you have to be careful, right? Because constraints can tip you over or they can be set at just that right point where and here's the difference. It's like if you're given a constraint and there's no part of your mind that can get to the point where you can save yourself. I see a way of making that happen or you're not confident about it or, yeah, you're just not confident in your ability to really do it. If you don't have that confidence or see a path to get there, a constraint can actually be paralyzing. And so you wanna ideally as a leader, you don't wanna, you don't wanna put those kinds of constraints in. But if it's the right constraint and the person receiving that constraint has the right attitude about it, you gotta have a positive attitude, right? Because also if you look at a constraint, even if you see a path to making it happen but you're negative about it, even your attitude is gonna affect your ability to hit that goal or to meet that constraint.

Gabriel:

100 percent.

Jason:

And for me, it was just enough because I always have this in the back of my mind this notion that it's gonna work out, you know? So in the back of my mind I always have this positive like glass half full kind of mentality that it's gonna work out. So usually if I'm given a constraint, I'm just heads down on it and even if it's really tight, I can see some kind of path or I tell myself we're just gonna try as hard as we can and something may happen, we might get there. We don't know, you know, it could happen at the last minute. It could happen. So, one of the things that I like to do is embrace constraints, you know? A lot of people can see constraints. And then they get immediately negative, you know? And then the attitude pervades and then the attitude actually ends up being an obstacle to your performance and to be able to make it happen. So embrace constraints.

So I embraced the constraint and… and I was like, we don't have as much budget and our goals are starting to increase. And so my first thought was I need a free channel that I can leverage quickly to start driving demand and I immediately went to email, of course. So nowadays there's very easy ways to buy emails. You know what I mean? Email addresses if you need to. If you've got a subscription with ZoomInfo or Sales Navigator you can really get access to email addresses, business email addresses.

But given my ops background, I hate email because if it's trackability or lack of trackability. And the reason I say that is we all think email is highly trackable. It is. But the problem nowadays is that enterprises all the way down to even small mid sized businesses have email spam filters now that don't just stop the email from getting there. It actually opens the email. It clicks through all the links in the email. And so your marketing automation system thinks “Oh look somebody opened. And what you can do is you can see some of the data when you send the email. And like three seconds later you get all these opens and clicks, you like, yeah, probably not somebody just sitting by their email waiting for a marketing email to come in and clicking all the links real quick. And so I was like, I don't wanna use email because I never really will know what's working and what's not. Not like I might know at the very bottom end of it, right? Because somebody is going to then request a demo and I'm gonna get their information and I'm gonna maybe understand that it came from email but all the early metrics, my leading indicators, is the subject line right? Is the pre header right? None of that is really going to work. So then I was thinking, hey… what about LinkedIn InMail?

Because I was thinking, I get InMails every once in a while, but usually it's from a salesperson or it’s from a recruiter. And I was thinking, well, what if I have the email come from me as a marketer and just went to other marketers? Like people wouldn't expect that. So I'm always trying to think like what? Because again, the marketing to marketers… marketers can be very difficult to break through with because they know all the things. I don't like to call them tactics because tactics makes it sound like I'm like plotting and planning and scheming to try it. But they know all the tactics, you know, the marketers do. But what gets a marketer excited, well me included, is when I see something new that's interesting that I'm like How did they do it? Or I'd like to be able to do that! And so… I was like, okay, we're gonna try InMail, I got theInMail ready to go. I have my target ready to go and...

Gabriel:

And this was sending yourself on behalf of the sales team. So if the person replies, you're just gonna, you know, route them over to your sales directors and your sales account executives.

Jason:

Exactly. So it's basically, I wanted to see, hey, can I outbound as a marketer? You know what I mean? So basically, will that be a viable tactic which I thought it would be. I was just thinking to myself as I go. I would respond to a marketer coming to me telling me like, hey, they use their own product to help them out from a marketing perspective. Let me hear about that. It's ideal. It's somebody that I can make a connection with and kind of build some trust pretty quickly.

But then when I logged in to LinkedIn to build the ad, I saw this beta product that said Conversation Ads and I was like what's this? And that's basically where I got introduced to Conversation Ads and it was like it's basically like a “Choose your own adventure” like, Drift style, Intercom style bot playbook, but delivered inside of LinkedIn using LinkedIn’s ad targeting network or capability.

And so my thinking was… and especially with the cost because I'm like, okay, you know, it's going to be 55 60, 80 cents to send and like, hey, I'm willing to pay that to get out of the email realm to do something a little bit different. But then to have the laser targeting capabilities of LinkedIn kinda sitting on top of it. And so I went back to the drawing board and was like, now I can create an actual Conversation Ad. I can plan out a strategy.

And so my strategy was… we had low awareness at the time. And these messages, you get 500 characters for each message. So I have to quickly establish rapport. I have to be relevant to them. So I'm somebody that understands your pain. And then I need to show some social proof because we don't have very good awareness. And then I need to try and get you in the funnel. But with further qualification and this ad type really allowed me to do that. So I can just generate interest, give them some social proof, and get on their level. I'm a marketer just like you. I've got aggressive pipeline targets to hit. Guess what, I use my own platform to do that. Would you like in? Would you like to see it? And that was really it. And we started running it and it just took off. It really just took off. I think I went from like 39 or 40 demos in March to 130 or 160 in April. So in one month… and then it just kept going from there. And so we really leverage that channel and that campaign of course, with different iterations and optimizations and audiences for the last year and some change.

Gabriel:

So keep doubling down on the format for what works, right?

Jason:

Exactly

Gabriel:

If you took a step back, right? Let’s pause here at this point - just before the success, right? When you identified this channel, decided you're going to run an experiment on this. I'm interested to know, (A) how did you message this to your boss, your CEO. “Hey you know I have this crazy idea, we’re going to try this? And how did you message this to the sales team, “This is what marketing is trying to do”. How did that happen in the background?

Jason:

Yeah well, one of the big benefits that I have is that our CEO, he built our product to do experimentation. So he's all about experimentation. And so he probably pushes me more. He pushes me to do more experimentation than I would probably be even comfortable with. Which I really appreciate because it helps us find some new interesting things to do. So really, I think the only idea he's ever said no to me about is when - so the pandemic was starting to kind of fully roll and there was a toilet paper shortage, right? I actually got Sendoso to source toilet paper rolls and I was gonna send toilet paper out as a gift through Sendoso’s gifting platform. But later on, this is right in the heart of it. I was like This is edgy, I don't know how people will receive this. If they're like me, they'll find the entertainment value in it. But we kinda pooh-poohed that I wouldn't say (my CEO) was the one who pooh-poohed it, but he was like, I don't know about that. You can do it if you want, but I don't know about that. And sure enough, we didn't do it.

The sales team were welcoming at that point. So part of the offer is if you qualify, because we go through a pretty strict qualification. If you qualify, we'll give you a $100 Doordash gift card and this is again during the pandemic people are cooking at home and they’re tired of cooking at home. And so this is also an interesting part of the offer. Give you a Doordash gift card, $100, in exchange for your time on a demo if you qualify.

So at first before the campaign started running, I was worried about the 100 dollar offer. Is that going to cause people to fake the interest just to come in and get 100 dollars? So that's what I was worried about at first. So it wasn't until leads starting to come in and the meetings started to be had that the sales reps were like, wow, like, hey, we're getting some good titles in here because again we could really laser target and the conversations are actually good. And half the time people aren't even remembering about the gift card. And that's what I was hoping would happen. Now I… I made sure the sales team knew don't ever make them ask for it. So if you have it just immediately just send it. So I don't want to have somebody. Hey, where’s my gift card and put somebody in an awkward position.

But we started noticing that and that was a good sign, you know, that like they're forgetting about it sometimes, you know, because they're actually interested. And then of course, we have some tyre kickers that would come in and pretend like they're interested, but there only for the gift card, but it was such a small percent. It was okay and the sales team was okay with it because of the number of quality leads that they were getting. We also had our SDR team that would further qualify them. So I qualified them pretty strictly in the ad, but then just to make sure if their title was a little bit more junior, the SDRS would dig in a little bit more just to really make sure, and they would do it in a really gentle way but they would then disqualify some more people that way before then they ended up in the hands of sales.

Our whole company is really all about trying, trial and error, failure is okay. So that's one thing though when it comes to experimentation, it's a cultural shift first. So you can't be a marketer who's all about experimentation and enter a company that doesn't have a culture where it's okay to fail. Because if the culture doesn't support it, experimentation means failure. You know what I mean? The definition if you look it up. But if you say I am an experimental marketer, it means you fail a lot and you're okay with it. And you know how to iterate on that and come back from it.

And I've been a part of orgs too where everyone says they're okay with it. Yeah, of course, experimentation failure is going to happen. And then when you're doing it, they get anxious, they meaning the people, not just the cmo. They get anxious. They get nervous. And then oftentimes it's like that muscle memory, they go back to what they know, they go back to what they know has worked, they devalue experimentation and you move back to an activity based set of goals versus a performance based set of goals. So, you know, one thing is, you can talk a lot about, we want to experiment. We need to experiment. It's the right thing to do. The company culture has to support it first.

Gabriel:

How do you test for that? So assuming that you're a marketer today, right? You're looking for a new job, you want to join a new team and like you rightfully stated, right? No one in the meeting is going to say we are not innovative, we don’t experiment? Everyone's gonna say that, yeah, we experiment, we're innovative. But what are some of the questions that you can ask to turn the tables on your interviewer to get the ground truth on the company's culture?

Jason:

Yeah, that's a good question. You have to triangulate it. In my experience, you kinda have to triangulate because you're right. Every individual you talk to, they will have their own kind of flavor of like, well, yeah, we, you know, we experiment. But you might get one answer from sales and another answer from marketing and another answer from product. And so you kinda wanna, you want to be able to meet with several people and really understand it.

Another good sign though is if your CEO happens to have ever been in marketing, usually that will, now that's the double edged sword though because like if they've been in marketing then they often come with a lot of ideas that they think are good or will work. And sometimes maybe they haven't been in marketing for a while and they're not really great. But on the benefit side, they understand the difficulty of marketing and that if they've been in that role, they wanted to experiment before. And so oftentimes just where the CEO came from. If they come up through sales, what's most probably most CEO'S do, then it's definitely making sure like how do you value marketing? And then looking at the size of the org compared to the rest of the company. So if you're coming into a Series C company that's got 100 plus employees and the marketing size is 3 or 4, that would be a warning sign in my mind. Where's the proof behind the fact that you value marketing. So I think it's starting with, how does the company value marketing? That's the first gate you need to get through.

And then the second one is… can people fail and still be respected here? Do you have to come in and prove yourself first? And then do it. You know what I mean? It's like the old, funny thing like when you go to jail, like come in and punch the strongest person first to show you belong there. So nobody messes with you? Hopefully not although that always helps. It doesn't matter what culture you come into. If you have some quick early wins, that is always gonna help you but you want to know that that's going to be okay.

But like you're gonna miss on some things. You're gonna waste some money. It’s going to be considered a waste, but it really isn’t. If you're learning then it's not a waste really but you're going to spend some money that doesn't result in revenue, you know? And I think in an environment like that, there needs to be a lot of trust. So I think just really understanding the relationship culture within the company, do we have personal relationships outside of the work relationships? And do we base our trust on those relationships? Because then, you know, you can always kinda come back to that even if things aren't always working out perfectly in the numbers. So it's not easy. I've joined orgs where I didn't do that upfront work. And I was sad at the back end, ended up having to quit because I didn't see eye to eye, didn't have the same thoughts on failure, experimentation, those kinds of things.

Gabriel:

Yeah, I totally hear you. So much of modern marketing because of how fast things are changing, It's so crucial that you have a culture that supports and nurtures this whole spirit of experimentation.

So switching gears a bit and coming back to the really really successful experiment that you guys ran, what advice would you give for other marketers to come up with similar crazy ideas like you right now. How do I get this lightning bolt, that one day I'm going to run like Conversational Ads, I’m going to offer people a Doordash gift card, what's that process like? How do ideas like this get bubbled, prioritised, sorted, and go from idea to fully funded experiment?

Jason:

Yeah. So one of the things that you need is you need to probably start with your budget a little bit. So, okay, you know, the first thing you wanna do is you want to understand how much of my budget do I have, to experiment with that doesn't need to work? You know, what I'm saying? You don't need it to hit your goals.

Gabriel:

Like your discretionary budget?

Jason:

Exactly. Yup… yup. So hopefully you have enough budget with your historical tactics to meet your goals and still have a buffer in spend.

Gabriel:

How do you proportion it? Like 80 percent/20 percent, 30 percent/70 percent. How do you think about this?

Jason:

It is custom every single time and for me almost every single month too. And so what I do is I start with a demand model that basically I work backwards and say, okay, this quarter, we have this growth delta within the company. You know, we're going from $1 to $2M let's say, so, okay, I've got a growth delta of $1M. Then I use math to basically in historical rates to tease that back to how many opportunities, you know, how many opportunities do I need? How many leads do I need? How many demo requests do I need? And then I have an average CPL that I understand to get to that goal. And so if I do the math and let's say my budget is $30,000 for a month and I've done the math and I'm like, okay, I can meet my minimum goal with $25,000 dollars of that.

You know, again, to the best of my knowledge from historical data and what I know I'm going to do. So then basically that's the easiest way to say, great I have $5,000 to test with because I don't need it to meet my goals. And so then that's the easiest way if you end up having a buffer and if you know some of your unit economics.

Gabriel:

That makes a tonne of sense. But I guess the danger with this then comes if you are falling behind your goals, right? And then now shit. Every single dollar matters. Do we still want to carve out money for experimentation? How do you think about that?"

Jason:

Yep. So that's the second way, which is not as fun. This is probably the majority of people are living in this world where it's like, well, yeah, I'm looking at my goals and man, I might even have less money to get there than I think I need. Then it actually takes some faith and some confidence. And it's almost even more important at that point. So, if you work your numbers up and you realize I need $40,000, not $30,000, then you kind of already know even if all this stuff works out like I think it is, I'm still not gonna hit my goals.

Then you're like, well, I already know, I'm not gonna hit it with historical stuff in the past, tried and true things I've been doing. So I need to experiment. So in that case, then it's almost like an efficient frontier. You wanna see like, well, how much can I spend of this budget to get like the most efficient leads in the historical and kinda tried and true stuff? But then try and reserve 20% or more especially if you're in this negative like inverse situation where you don't think you're going to be able to hit with what you have. 20% or more because you need to put your best foot forward on these experiments to really see if they're gonna work out. So, one of the worst things that you can do in experimentation is half ass it. There's a difference between half assed and an MVP. What you want is an MVP, but that MVP, you need to be as close to the end experience that you're going for, so that you can actually put your best foot forward.

Gabriel:

Give me an example of what does a half-assed experiment look like.

Jason:

So a half assed experiment would be a new random direct response offer to just a broad broad audience. So let's say just say like, okay… I just need some hasty demand. I'm just gonna throw up a demo request campaign. I'm just gonna toss it to the most audiences I can. Well, you're probably wasting some audience. You might have already hit them before you. That's actually probably not the best example of a half assed. Let me give you a better example. That's just an example of like I'm really running behind tactic.

But like a half ass on an experiment would be… let's say there's a critical aspect of the offer that you need to have happened. Let's say if something freemium you know what I mean? Like something there's like some kind of free trial or free thing that you want… half assed would be either that free trial experience doesn't really even do justice to your products or maybe even down selling it. So let's say you're like, well, I can't really get them into the product but I'm gonna get, I'm gonna create like a separate environment and that environment is going to be, it's going to have limited features and it's not going to be a true environment but it's going to give them more of an experience. Well, you actually might be doing yourself disservice. You know what I mean? By saying? Well, at least they can try it. Well, there might have been actually more benefit in the curiosity, what is like and then getting a demo, then just turning somebody onto a demo environment for example. So that could be one where you're like, well, you have all these excited ideas. Well, yeah, we just had a freemium offer or like some kind of free trial. We'd be good. You put that free trial and it doesn't panel the way you think it is because the actual experience in that free trial isn't the same as what it would be in the product. So that would be an example. I'd say about a half assed one.

But there's an MVP way of doing it for example where you still aren't going to deliver the entire experiment, like what the end campaign would end up looking like but you're going to deliver just enough of it to where you can understand, is this going to be a viable way to get demand. And so an example of that would be a very easy example would be trying to email first for something. Okay. And just having them reply to you instead of going to a landing page et cetera. So an easy way to do that would be, alright. I have a set of prospects that I think have a specific use case or a complimentary product or something I know about them, but I want to message them, right? I'm just gonna email them. And instead of saying, go register for this on the landing page or whatever, I'm not even I'm just gonna try and put my message in the email. Hey, if you're interested, just reply to me. Great. Well, and then you send it to a limited number of people, 1,000 people, just enough to where you can see like, is this going to be interesting? Is this offer going to be interesting to that audience? And then if it is great, let's expand the acquisition part of it. Let's expand the offer, let’s make it a little bit more formalized, let’s build a landing page to tell more about it. And then the expectation is no matter what, it's going to perform better than your MVP. And you’re just gonna add onto the MVP. The MVP would be like your most conservative view of what would happen. And if that looks promising, then it gives you like that license to say, Let's go actually put the resources behind and build out the rest.

Gabriel:

Nice. This is gold. This is gold right here. So if you could summarize in one to two sentences, How would marketers know if they are half-assing something or they are making a very calculated MVP, you know, a version of a campaign, how would I know?

Jason:

Trust your gut. This one’s really kind of gut. There’s a little bit of gut. Here’s the way I do it now and it's taken me 40 years to get to this point. If I have literally any qualms about something in my mind, if I'm like I don't know if that, I pause, I just pause and I rethink it. Because what I'm trying to avoid is I don't want anyone that's in my funnel to think that they got there in some weird backhanded bait and switch you way. I want it to be so authentic and straightforward all the way through it.

And so, keeping something like that in mind and keeping in mind that… at the end of the day, would I feel comfortable standing up and presenting this to a whole set of customers, prospects, my CEO, would I feel really good about it and would I feel really good about like… providing every single intricate detail about how I got somebody in there, what they're going to convert. It's a lot of a gut feel… but this is the balance between quality and speed, right? And you have to understand when enough is enough. I've worked with so many people in my career that don't have that, right? And I am actually one of them, in some cases, I'm actually one of those people were… my view of what's done enough is gonna differ from my CEO'S view for example. And so I think being open to flex a little bit but having a line of where like, okay, we're not gonna go beyond this line and we're not going to go below this line.

It's just good for your brand as well. You know, because you don't want your brand to seem like it's just trying to test a bunch of stuff, radically. Everything that you do also has an impact on your brand. So you want to really be considering (a) the number of experiments that you're running at any given time. But also, and this is really where it comes together is like being really formal around how you manage the audiences that are seeing the different experiments. So what you don't want, you don't want to intermix audiences across a bunch of different experiments to the point where they're in that I've done this exact same thing. So I had one door dash offer that was for 100 dollars. I had a 200 dollar Amazon gift card from a separate one. I bled the audiences. Two or three people came to us and was like, well, I have the 100 dollar one now but two weeks ago, it was 200, you know. And as a different offer, I don't understand. That’s not a great experience for my brand.

And also I'm selling marketing advertising software, right? And so if I'm getting that wrong, they're gonna assume I'm using my own software, which I do. Now, it wasn't my software's fault. It was my strategy's fault. But being a marketer of marketing software, I have to be really careful with that because again people are gonna just make the leap. Well, he's using his own software. So if he's making these mistakes, is it the software that caused that or is it him? And so that's just one of the examples then where I've gone wrong too. So everybody out there listening. Sorry, if you've got more than one Conversation Ad from me with different offers in it. My bad, 100%. My bad. I don’t blame LinkedIn.

Gabriel:

I love this… this is so authentic. You’re so vulnerable in sharing your mistakes. AI would like to double click a little. Into this whole formal segmentation of the campaigns. And if you zoom out just one more level higher, how do you think about formalizing this whole culture of experiments? Not just the segments that you go after, but the kinds of experiments that you run, how much budget, what’s the success criteria. The last time that we were speaking, you said that you were trying out this new framework that you got from Guillaume Cabane. Can you share with us more about that?

Jason:

Yes, I love it. So like you mentioned, Guillaume Cabane is a mentor of mine from the Ops side. He is a Marketing Ops Whizz… and he's got so much energy too. I wish I had half his energy.

Through my mentorship with him, he showed me this experimentation framework that he was using. Probably a year ago he showed it to me. And I was like that's great. It's an Airtable. You know, I wasn't using Airtable at that time. Oh this looks amazing because again, I have an operations background. I was like, this is awesome. I want it, but I was a one person marketing team and this framework is fairly formalized. And so I was like I'm not ready for that. So I used my own stuff between last year and this year and finally this year it wasn't so much that I got a lot more time. It became actually a necessity because we started to do more experiments and just managing them ad hoc wasn't working well. You know, I was like this spreadsheet is in a sauna and, you know, where is this? How do we plan these out? How do we know what we're doing? And then even similarly important, how do I communicate what we're doing? How do we report on what we're doing? All this experimentation? And so what this framework does is it gives you a way to first collect all the ideas. What are all the ideas we have internally? But also you actually externalize the form to the rest of the organization. Your CEO, head of sales, just gives them a place to come and input an idea that they have.

Gabriel:

Hi, this is so much better. Right? Right now, I go to my team, Hey, I have this idea. Hey, I have that idea. And it drives my team crazy, right? Now with a formal way, Hey, Gabriel, put this idea into the form and we will stack rank them according to every other idea that we have.

Jason:

Yeah. And I have like seven different ways that (CEO) sends me ideas. He whatsapps me, he emails me, we talk, we lose track of it. So, just having a place to collect it all and have it there to start with, that's a big part of the pain. But then it gives you a way to add, what are your impact metrics? So what are the things you're trying to impact? So usually for a marketer its’ going to be demo request, site visits, content download, you know, all your like success metrics. You add those to the Airtable and you basically ideally, you have enough data. So you understand what's the relative revenue value for each of these activities. You know what I mean? So like, so you can ideally trace it back from a closed-won deal to an opportunity to a meeting to a stage opportunity. 5,4,3,2,1 demo request. The actual specific value is not as important as the difference and values between like your lowest touch KPI which is a website visit probably or an ad click, maybe even. And your highest important one which is probably a meeting booked or all the way down to closed won revenue. And so having those ordered. So you have your impact metrics. And then now you've got all your ideas.

Now you start to add data to your ideas. Things like, well, what metric is that going to impact? Behind that is, what does that equate to in revenue? How many more of these do I think I'm gonna get in a month or annually? What's my confidence level in that? So you add these data points? And then it basically turns it into how much revenue can I expect from this experiment? Now, it's not going to be exact. You're just looking though for a relative split, right? You just want something that's going to order them by the most important things to do. You also add, how many days is it gonna take to build? Because it's gonna take that into consideration too. So it's gonna float the highest revenue opportunities with the lowest effort to the top. And so you're automatically just gonna see the ones like the low hanging fruit basically.

Then you have different statuses of these experiments. Idea, impact scored, building, running, waiting on results. You've got these different statuses. And so then you start to assign things to different statuses and you basically assign them to a person. They go build them out. You run the experiment and you come back, you've got data associated with it. And then at the end of it, it's basically the decision is, do we promote this to be an evergreen kind of a thing that we just run or does it go to the graveyard because it didn't like it didn't meet the initial criteria. And that's really it.

And we started using this really recently. We were using a flavor of it. It was mainly just like how hard is this going to be to build and like impact? And that was really it. Now, we've got all these other data points and just other things to look at. Also, the surface area the experimentation is going on here. So in marketing, you have all these different areas that you can impact. The website - the biggest one, paid advertising, organic like social media stuff. Like there's just so many of these different specific areas you can touch. And ideally, you're running an experiment or two across each surface area any given time. Now, of course, your resources are going to make it partly dependent on that. But, you know, that way you can like easily see what do I have? Do I have at least one experiment running on the website right now? When was the last experiment we have on the website? Because, or what was the last time I ran an experiment to try and, you know, increase our organic reach? So you can kind of make sure that you're testing different things in areas that you know have an impact and spreading those out and not focusing too much just on like email, for example, too much on paid advertising or the website. You are spreading your time around.

Gabriel:

How do you run a cadence around this though? What is the cadence like? Do you guys come together every week to look at what new experiments to run? When do you close the loop on experiments? How do you think about that?

Jason:

We have a checkup meeting every week. And in that meeting with the broader team we are looking at, okay. Where are we at with these things? Do we have any results that we can talk about? Do we promote them? Alright? What's next on the backlog? Basically, you know, what do we want to assign out? We're starting to work in two weeks sprints basically on these things. And so we'll assign something to a sprint.

Gabriel:

Interesting. I like how you guys work in sprints similar to the whole engineering Agile yeah.

Jason:

Yeah, it's the best way I found. I've been using sprints in marketing for probably five or six years now. I have found it to be that because it's just hard to tell how long it's gonna take to build out in marketing. You know what I mean? So it's like try not to assign a hard date to everything but just moving things forward and then basically picking the thing that's going to have the next biggest impact and working on that especially with teams with limited resources. l don't know how you do it without agile.

So yeah, two weeks sprints… and we're just starting to get into that cadence. So basically at the end of a two week sprint, alright, what were we able to accomplish that we said we were, what didn’t we accomplish? Put what we didn't accomplish back into the whole backlog, reprioritize, reassign, start working on things. And that's some of the benefits of experimentation is that most of the things that you're going to be doing won’t have a hard date associated with them, right? Because it's usually optimizing something that's already out there or trying something brand new that's usually not tied to like a product launch date or, you know, some kind of deadline. Because like with events, product launches, that's on a cadence, you might want to try something new with one of those, but it's usually not like a time bound experiment.

Gabriel:

Got it. So when you mean that you guys operate on a two week cadence. So I totally get that right about, does it mean that each experiment runs for two weeks as well? Or not necessarily?

Jason:

Yeah not necessarily. So usually for me, I associate a budget to an experiment. So how much do I want to spend on this before I take a look before I pause it and look at results and decide if it's something that we're going to continue to do or not. Or if it's an MVP, then decide if we're going to fully build it out. And so ideally, I try and spend as much as I can as fast as possible because in my mind, it's gonna take the same amount of spend to get to the answer. Time is flexible, right? So, well, if it's gonna take me a 1,000 dollars to get to the answer, do I wanna spend that 1,000 dollars over 10 days or one day? Well, I want to spend it in 1 day so that I can get to the answer faster. And so I'm usually thinking about how much money do I want to spend on the experiment? And usually that's informed by some kind of data. Either, I know what my CPL has been in this kind of tactic before. It is a slightly different one. So, okay, I'll spend $1,000 dollars or if it’s brand new, I need to let it run for a little while, Okay, $5,000. Or something that we’re highly confident in that we just haven't done before, so you know, more money. So it's not just a blanket. Like every experiment. It's 2000 dollars. It's basically considered for each one. And based on what we think we're gonna be able to do with it.

Gabriel:

Got it. So how has having this more formal way of running experiments, this Airtable framework, benefited you personally as a Head of Marketing and your marketing team in general.

Jason:

Yet to be seen but here's what my expectations are. So beforehand, it was all ad-hoc. It was, we think we should be doing this. I think we should be doing that. I try in the beginning of the month to basically split out like, okay, here's my marketing budget here's. What I'm gonna spend on these things here's. You know, ideas for this. But we were too close to the month we were trying to effect.

So we weren't quite planning enough. But that's how everyone really needs to start. So you start with like the informal way of like trying things out and informally tracking things. But then you get to the point where you're like, well, this is just not working anymore, you know, and… and maybe either leaving money on the table. Or for us, it was we're having a hard time communicating what we're doing was one of the bigger challenges.

And so moving to the formal one, what it's doing is it's (a) it's helping to just visualize everything that we're doing. And in a way where it's not just all in one big list is actually broken out by here's the things that are in the backlog, here's what we're actually building. And then we can start to make sure that well is any one person overcommitted or are we just over committed as a team in general on some of this given other things we have to do. So just being able to quickly assess like do we think, you know, do we have enough experiments to run? You know, do we think it's reasonable to kinda get this stuff done? Looking at it making sure that the surface areas are covered? You know, I've got a visual that I can look at and make sure that's covered.

And then having a more formal way to get the learnings that the back end. So what do we learn from this campaign? What metrics did it impact? Did we meet the goals or not? If not, why do we think that was the case? And what did we learn so that we can inject that into future experiments? And that's the most that's one of the most important things that we weren't doing before. We would anecdotally remember in our heads, but that's like one of the worst places to have it is in your head because you'll know itt. But then as soon as your marketing partner tries to run something, they won't and they'll run the same problem again. And you're paying to learn something twice, which is what you want to avoid. So, yeah, that's how we approached it.

Gabriel:

Got it. This is awesome. Jason this was fantastic. I have learned a tonne. THere were a lot of nuggets in there that I think our audience can definitely find useful. Thanks so much for taking the time in this Masterclass and sharing with us your way and your approach towards experiments.

Jason:

I appreciate it. Thanks for having me on.

Co-founder & CEO at Saleswhale

Sign up for cutting edge ideas on conversational marketing, AI assistants and martech.

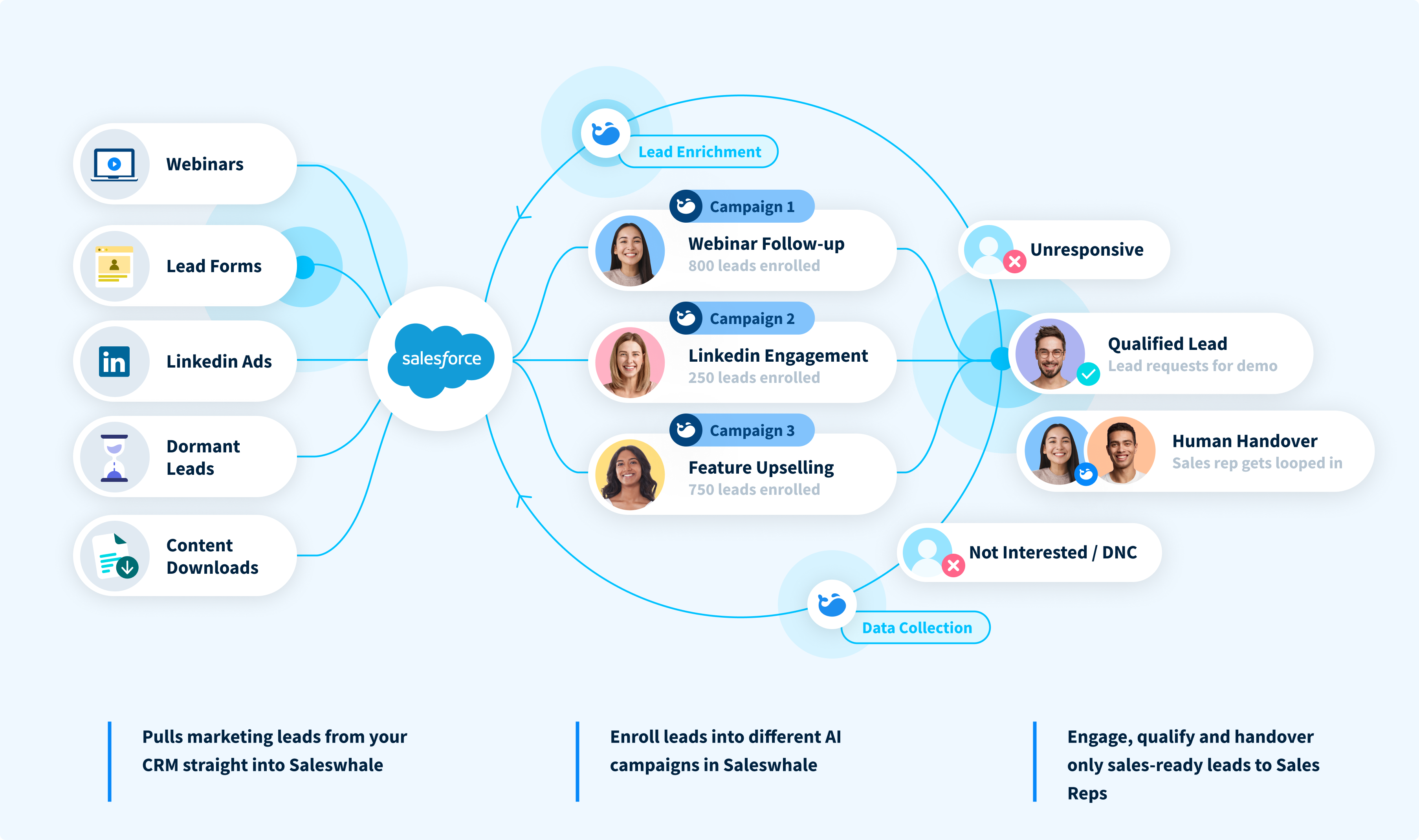

Saleswhale for Salesforce allows you to build powerful automated lead conversion workflows. This allows you to re-engage with your neglected marketing leads at...

19 APR 2021

Demand generation and marketing teams generate more leads at the top of the funnel than ever in this new digital-first world. Saleswhale helps ensure those...

1 MAR 2021

Marketers that focus on MQLs end up doing the wrong things in order to achieve the metrics. So I changed it.

16 JUN 2020

Conversica isn't the only player out there. Learn how Saleswhale and Exceed.ai compare and make an informed decision.

15 APR 2021

By providing your email you consent to allow Saleswhale to store and process the personal information submitted above to provide you the content requested.

You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the link in the footer of our emails. For information about our privacy practices, please visit our privacy page.